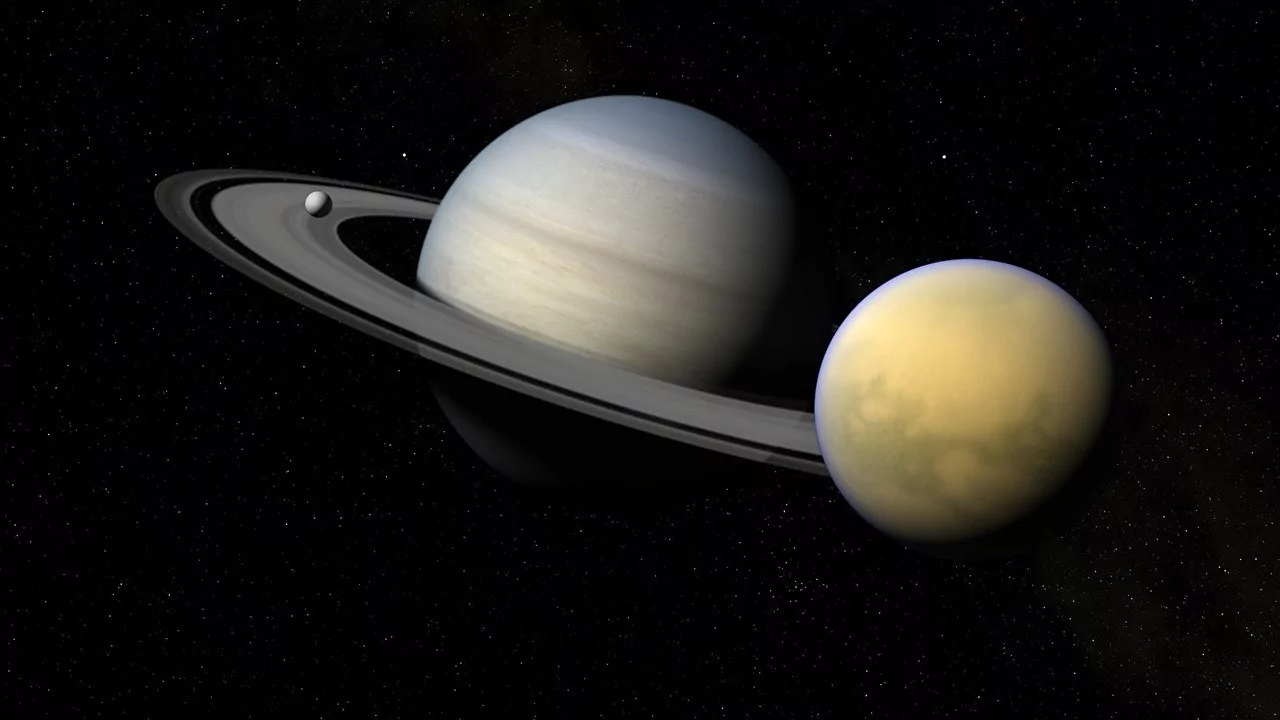

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is distinguished by landscapes very similar to those on Earth: rivers and lakes, canyons and sand dunes. The difference is that on Titan, this landscape is formed by radically different substances from those on Earth: liquid methane flows through the riverbeds, and sand dunes are formed by other hydrocarbon compounds.

For a long time, the scientific world could not understand how all these elements of the unearthly landscape were formed, and most importantly, how they were maintained. The fact is that hydrocarbon compounds are significantly more fragile in comparison with the silicon compounds prevailing on Earth. Nitrogen winds and liquid methane were supposed to turn Titanium deposits into fine dust, unable to form relief elements.

A group of scientists from the USA probably found answers to many questions. In their opinion, the landscape of Titan could have been formed due to a combination of agglomeration (sintering) of materials, the action of wind and the change of seasons. The key to the discovery turned out to be ooids — spherical or granular mineral deposits that are found on Earth. These deposits are formed as a result of the destruction of large silicate formations, for example, stones. On the one hand, various minerals are deposited on ooids, on the other, grains are subject to further destruction under the influence of water and winds. At some point, the processes of deposition and destruction balance each other, and the ooids retain a constant size, and when transferred by the forces of the elements to new places, they again form large structures.

Scientists have suggested that similar mechanisms may work on Titan.